When the body takes a hard hit—like a serious accident—the obvious injuries get all the attention. Broken bones, bruises, blood.

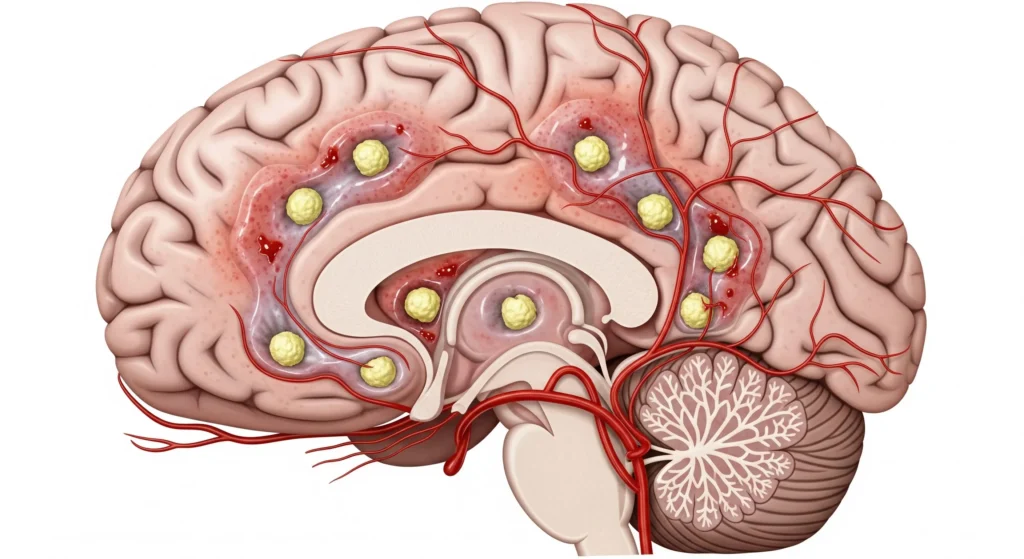

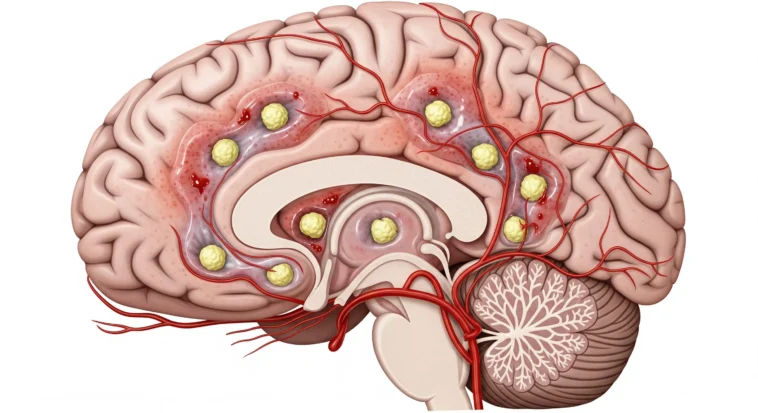

But sometimes, a much sneakier danger shows up later. It’s called cerebral fat embolism, and it’s one of those problems doctors learn to watch for because it can quietly mess with the brain.

What Is Cerebral Fat Embolism?

Think of it like this: after a big injury (especially broken bones), tiny fat droplets can leak into the bloodstream—kind of like grease slipping into a water pipe.

These fat bits can travel all the way to the brain, where they clog tiny blood vessels.

When that happens, parts of the brain don’t get enough oxygen, and that’s when symptoms like confusion, seizures, or even coma can show up.

Cerebral fat embolism is part of something bigger called Fat Embolism Syndrome (FES), which can also affect the lungs and skin. The brain is involved surprisingly often, which is why doctors take this so seriously.

How Fat Emboli Reach the Brain

There are two main explanations, and honestly, both probably happen.

Mechanical Theory

a broken bone squeezes fat from bone marrow straight into the blood—like popping a tube of toothpaste too hard. That fat can sneak past the lungs and end up in the brain.

Biochemical Theory

trauma stresses the body so much that it breaks fat into tiny toxic particles that slip easily into brain vessels.

Different patients, different mixes—but same danger. And that’s why after major injuries, doctors don’t just fix bones—they watch the brain like hawks.

Common Causes and Risk Factors

Here’s the deal: cerebral fat embolism doesn’t just pop up randomly. It shows up after specific kinds of injuries or procedures.

Orthopedic Trauma

This is the big one. Break a long bone—like your femur (thigh bone) or tibia—and you’ve basically shaken a bottle of bone marrow. Fat can leak into the blood and head straight for the brain.

The worse the break, or the more bones broken, the higher the risk.

Orthopedic Surgical Procedures

Even surgeries meant to fix things—like hip or knee replacements—can trigger this. Drilling into bone can push fat into the bloodstream, kind of like squeezing air bubbles into a syringe.

Surgeons are super careful now, but they still watch closely because this complication is sneaky.

Non-Orthopedic Causes

While less common, cerebral fat embolism can also result from:

- Severe burns affecting large body surface areas

- Liposuction and other cosmetic procedures involving fat manipulation

- Bone marrow transplantation or biopsy

- Pancreatitis with extensive fat necrosis

- Prolonged corticosteroid therapy

- Sickle cell crisis with bone marrow necrosis

Patient-Specific Risk Factors

Oddly enough, younger people (around 20–30) are at higher risk.

Closed fractures (where the bone doesn’t poke out), delayed surgery, and just letting a fracture heal without stabilizing it can raise the danger.

Certain blood conditions and medications can also change the odds.

Recognizing the Signs and Symptoms

This is where things get serious. Cerebral fat embolism is sneaky—it usually doesn’t show up right away.

Most of the time, symptoms hit 1 to 3 days after an injury, just when everyone thinks the danger has passed.

The Classic Triad

Doctors look for three big warning signs—think of them as the body screaming for help:

- Breathing trouble – fast breathing, shortness of breath, low oxygen. Often the first clue.

- Brain changes – confusion, agitation, seizures, even coma. This is where families say, “They’re not acting like themselves.”

- Tiny red rash – little pin-dot spots on the chest, neck, eyes, or mouth. It looks harmless… but it’s not.

Neurological Manifestations Specific to Cerebral Involvement

When fat reaches the brain, things can go downhill fast:

- Confusion, zoning out, or acting strangely

- Headaches, dizziness, or sudden seizures

- Weakness, numbness, or vision problems (sometimes it looks like a stroke)

- Extreme cases: loss of consciousness or coma

Some symptoms are spread out and vague, others hit one spot hard—it depends where the fat gets stuck.

Diagnostic Approaches

Diagnosing cerebral fat embolism presents significant challenges because no single definitive test exists, and the condition must often be distinguished from other post-traumatic complications.

Clinical Criteria

The Gurd and Wilson criteria, established in 1974 and modified by Schonfeld in 1983, remain the most widely used diagnostic framework.

According to these criteria, diagnosis requires the presence of at least two major criteria or one major criterion plus four minor criteria.

Major criteria include:

- Petechial rash

- Respiratory insufficiency

- Cerebral involvement with no other explanation

Minor criteria include:

- Tachycardia (heart rate above 110 beats per minute)

- Fever above 38.5°C

- Retinal changes showing fat emboli

- Kidney dysfunction

- Anemia or thrombocytopenia

- Elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- Fat globules in urine or sputum

Imaging Studies

An MRI is the MVP here. It can show a cool-but-scary “starfield pattern”—tiny bright spots scattered through the brain where fat has blocked blood flow.

CT scans are faster but often miss the early damage.

Laboratory Testing

While no laboratory test confirms cerebral fat embolism definitively, several findings support the diagnosis:

- Decreased platelet count and hemoglobin levels

- Elevated lipase levels

- Presence of fat globules in blood, urine, or cerebrospinal fluid (though detection is technically challenging and not routinely performed)

- Arterial blood gas analysis showing hypoxemia

Treatment and Management Strategies

Here’s the honest truth: there’s no magic antidote for cerebral fat embolism. No superhero injection. Treatment is about supporting the body hard and fast while it fights its way through.

Immediate Supportive Care

This is where lives are won or lost.

Respiratory Support

Oxygen is everything. If the brain doesn’t get oxygen, it panics—and brain cells don’t forgive easily. Many patients need extra oxygen, and some end up on a ventilator.

Think of it as giving the lungs a power assist so the brain doesn’t suffer more damage.

Hemodynamic Stabilization

Blood pressure matters. Too low? The brain starves. Too high or too much fluid? The lungs flood. Doctors walk a tightrope here, carefully balancing IV fluids and medications to keep blood flowing where it’s needed most.

Neurological Monitoring

This means constant check-ins with the brain. Are the eyes reacting? Is the patient waking up? Moving arms and legs? In severe cases, doctors even monitor pressure inside the skull—because swelling brains are very bad news.

Pharmacological Interventions

This is the “maybe helpful, maybe not” zone.

Corticosteroids

Steroids are controversial. Some studies suggest they might reduce how bad fat embolism gets if given early, especially in high-risk patients.

Others say the benefit isn’t clear. Doctors use them selectively—not casually.

Anticoagulation

Heparin sounds smart on paper—it might help break down fat—but in trauma patients, bleeding risk is a huge deal. Most of the time, the risk outweighs the reward.

Albumin infusion

Albumin can bind fatty acids, sort of like a sponge. Cool idea, limited proof. Sometimes used, never relied on.

Surgical Considerations

This is where prevention really shines.

Fixing broken bones early—ideally within 24 hours—dramatically lowers risk.

Surgeons now use smarter techniques to avoid squeezing fat into the bloodstream, like gentler drilling, pressure-release holes, temporary external fixators, and washing out the bone canal.

Prognosis and Long-Term Outcomes

Cerebral fat embolism can be scary, but it’s not always a life sentence.

Outcomes range from “back to normal” to long-term challenges, and a lot depends on how fast doctors catch it and how badly the brain was hit.

Studies show that about 5–15% of cases are fatal, and brain involvement is the biggest reason outcomes get worse.

For survivors, recovery is a mixed bag. Some people bounce back in weeks or months like nothing happened.

Others deal with lingering issues—memory slips, trouble concentrating, weakness, or personality changes.

This is where rehab becomes the unsung hero. Physical therapy, brain exercises, and occupational therapy help the brain relearn skills, kind of like leveling up after a tough boss fight.

The good news? Younger patients, early treatment, good oxygen levels, and smaller brain injuries all stack the odds in your favor.

Prevention Strategies

Given the serious nature of cerebral fat embolism and the limited treatment options available, prevention assumes paramount importance in at-risk populations.

In Trauma Settings

- Early fracture stabilization, preferably within 24 hours of injury

- Gentle handling of fractured bones during transport and examination

- Adequate immobilization of fractures before transfer

- Use of appropriate surgical techniques that minimize intramedullary pressure

In Surgical Settings

- Proper patient positioning during orthopedic procedures

- Gradual, controlled reaming of medullary canals

- Use of cementing techniques that reduce fat embolization during arthroplasty

- Maintenance of adequate hydration before and during surgery

General Preventive Measures

- Prompt treatment of multiple trauma patients

- Close monitoring of high-risk patients for early signs of fat embolism syndrome

- Consideration of prophylactic corticosteroids in selected high-risk cases, though this remains debated

Conclusion

Cerebral fat embolism is rare—but when it shows up, it means business. It’s one of those complications that hides in the shadows after big injuries or bone surgeries, which is why awareness matters so much. Miss it, and the brain can pay a heavy price.

Medicine is still leveling up with better scans, better prevention, and better care. Until then, the best defense is simple: stay alert, take symptoms seriously, and speak up.

If someone you care about has had major trauma or surgery, asking questions and watching closely can make all the difference. Brains are precious—protect them.

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings